Wales Day Tour

World Class Geology In Our Backyard

A Geology tour of the Blaenavon Industrial Landscape UNESCO World Heritage Site & the Fforest Fawr UNESCO Global Geopark

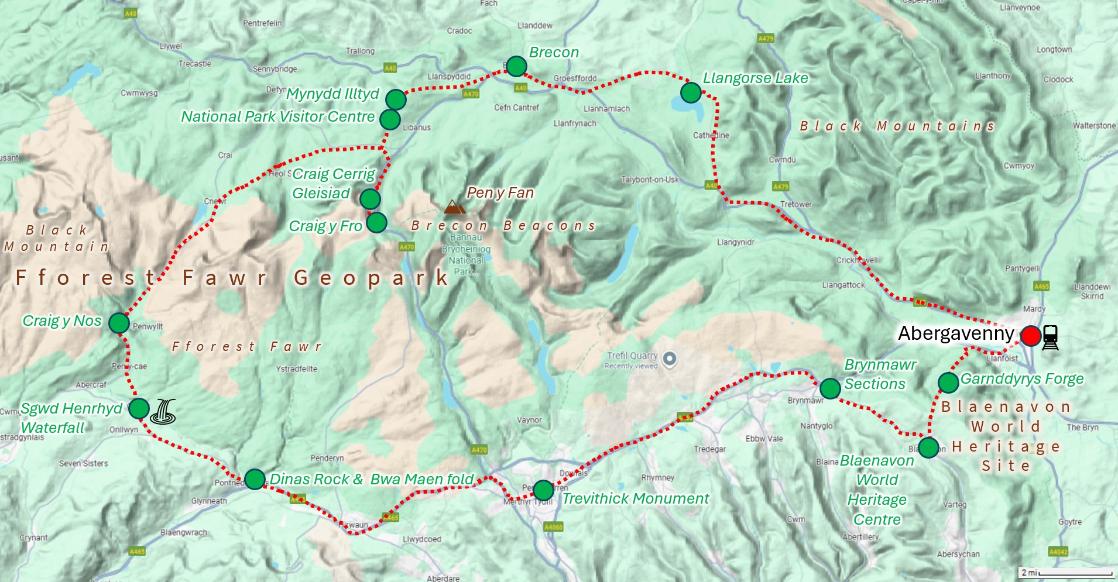

Start/ Finish location: Abergavenny

2026 dates

Wednesday 13th May

*4 spaces*

Tuesday 23rd June

*2 spaces*

Wednesday 16th September

*4 spaces*

£78 per person

Based on a minimum of 2 people (£156 minimum price)

INCLUDES PICNIC LUNCH & GEOLOGICAL GUIDING

Duration: 9am - 5:30pm

Number of places: 2-4 (or more if using your vehicle)

GeoWorld Travel leads geology tours across the world — from Antarctica to the Arctic — but this one stays right at home, because the geology here is exceptional. Within a single day, we explore classic Devonian and Carboniferous landscapes that underpin the mountains, caves, waterfalls, and industrial heritage of the Fforest Fawr Global Geopark and the Blaenavon Industrial Landscape World Heritage Site, both set within the Bannau Brycheiniog / Brecon Beacons National Park. This is a small-group day tour with a picnic lunch and plenty of walking, but no geological background is required. It’s a chance to spend time in the field with James, exploring the geology of the place he knows best — the landscape he lives in and cares about most. For those who are interested, it also provides an easy, informal way to get to know the person behind GeoWorld Travel while sharing a full day out in the hills.

This tour takes place in our backyard: GeoWorld Travel is located within the Fforest Fawr Geopark, additionally and our home office is located just outside the Blaenavon World Heritage Site. Both locations are within the Bannau Brycheiniog (Brecon Beacons) National Park.

A type Carboniferous System view with Old Red Sandstone, Mountain Limestone, Millstone Grit and Coal Measures in sequence

Blaenavon Ironworks World Heritage Site (drive-by not a stop).

Brynmawr Sections geological SSI here iron stones and coal can be seen in situ.

Trevithick Monument in Merthyr Tydfil commemorates the world's first train journey

Dinas Rock is a prominent Carboniferous Limestone outcrop that was once a rounded hill topped by an Iron Age fort.

The National Park is underlain by the largest cave network in north west Europe, this tiny cave in Dinas Rock is linked to the legend of King Arthur's resting Army.

Bwa Maen Fold, the 'Stone Bow' is a spectacular Variscan fold in the Carboniferous limestone

Fossil trees in mid Carboniferous rocks on the path to Sgwd Gwladys waterfall

Sgwd Henrhyd, the hihest waterfall in the National Park and Geopark.

Fossilised Devonian river channels in Craig y Fro quarry

Glacially eroded scenery in Craig Cerrig Gleisiad

From Mynydd Illtud we gain wide views of the Brecon Beacons, including Pen y Fan (886 m), the highest peak in southern Britain.

Llangorse Lake, the largest natural lake in southern Wales with the Brecon Beacons in the background.

GeoWorld Travel's Director James Cresswell is an accredited ambassador to the Fforest fawr Geopark

ITINERARY

Abergavenny: The tour begins at 9:00 am in Abergavenny, with pickup either at Abergavenny railway station, a car park in the town, or your hotel in Abergavenny. As we leave the town, we pass the site of its Roman fort, Gobannium, and its medieval stone-built castle. Shortly afterwards, we enter the National Park and the Blaenavon World Heritage Site. We cross the Monmouthshire & Brecon Canal, with a brief glimpse of Govilon Wharf. In the nineteenth century, this canal was the main route for transporting iron from the industrial uplands above down to the South Wales coast for onward shipment. Our route then climbs a long, sustained hill — known locally as the Keepers and to cyclists as the Tumble — on the flank of Blorenge, to reach our first stop: an impressive viewpoint just above the remains of Garn Ddyrys Forge.

The Carboniferous System and Garnddyrys Forge: At our first stop, we take in impressive views over the site of the former Garn Ddyrys Forge and the surrounding landscape. This is a classic, large-scale view of Carboniferous stratigraphy, where the major rock units can be seen stacked clearly in the landscape. The Carboniferous System takes its name from the coalfields of England and Wales, but it does not have a single, formally defined type section. In 1822, William Phillips described the Carboniferous succession as a sequence of Old Red Sandstone (now known to be Silurian and Devonian in age), overlain by Carboniferous Limestone, then Millstone Grit, and finally capped by the Coal Measures. From this viewpoint, all four units can be recognised in the landscape, effectively giving us a textbook view of the Carboniferous system as it was originally understood. The dominant mountain in the view is Sugar Loaf Mountain, composed of Devonian Old Red Sandstone. It is separated from the main plateau of the Black Mountains by the Neath Valley Disturbance, a major fault zone that runs from near Hereford to Neath, and which we will examine directly later in the day. Within the Carboniferous Limestone beneath our feet lies an extensive cave system. The Brecon Beacons National Park overlies the longest cave network in north-west Europe, and directly below this viewpoint lies Ogof Draenen, the second longest cave in Britain. Although invisible from the surface, it is developed entirely within the same Carboniferous rocks visible in the surrounding hillsides. Immediately below the viewpoint lie the remains of Garn Ddyrys Forge, an iron foundry that operated from around 1817 to 1860. Pig iron was brought here from Blaenavon Ironworks along Hill’s Tramway and worked into iron rails. By the 1840s, around 450 people were living and working at Garn Ddyrys, illustrating how closely the industrial history of the area is tied to the underlying Carboniferous geology.

Blaenavon World Heritage Centre: Our route then descends into the town of Blaenavon. As we approach, we gain views of the headgear of Big Pit National Coal Museum and pass the historic Blaenavon Ironworks, one of the most important iron- and steel-producing centres of the Industrial Revolution. In the late nineteenth century, work carried out here — at a time when James’s great-great-grandfather was the general manager — contributed to solving the long-standing problem of removing phosphorus from iron during steelmaking, a world-changing development that allowed modern steel industries to develop across Europe and North America. We stop at the Blaenavon World Heritage Centre, where there is time to read the interpretation panels, place the wider industrial landscape into context, and use the facilities.

Brynmawr Sections: Our next stop lies on the southern boundary of the National Park, near the town of Brynmawr, the highest town in Wales. The site, Brynmawr Sections Geological SSSI, is protected as a Site of Special Scientific Interest because it preserves a clear and accessible exposure of the Upper Carboniferous Coal Measures. The main face exposes the seatearth floor of the Five-Feet (Gellideg) Coal, which forms the uppermost bed of the section. The coal seam itself crops out in the recess immediately above, while associated ironstone bands and mudstones are visible lower in the exposure. Together, these beds record a complete Coal Measures cycle: soil formation, swamp development, peat accumulation, and burial.

Trevithick Monument, Merthyr Tydfil: We travel west along the newly upgraded Heads of the Valleys road, where a series of modern road cuttings briefly expose aspects of the underlying geology, before reaching Merthyr Tydfil, which lies just outside the Geopark boundary. In the early nineteenth century, Merthyr Tydfil was home to the world’s four largest ironworks, a concentration made possible by the local geology, where coal, ironstone, and limestone all occur in close proximity. The town is associated with several industrial firsts, including the world’s oldest surviving metal railway bridge (closed and under restoration at the time of writing) and the site of the world’s first journey by steam-powered locomotive. As we pass through the town, we stop briefly at the Trevithick Monument, which commemorates Richard Trevithick’s pioneering locomotive run here in 1804.

Dinas Rock & Bwa Maen fold: After leaving Merthyr Tydfil, we enter the Fforest Fawr Geopark near Pontneddfechan and stop at Dinas Rock. Dinas Rock is a prominent Carboniferous Limestone outcrop that was once a rounded hill topped by an Iron Age fort, later quarried to leave the cliff face beside which we park. From here, we walk along the River Sychryd, following the line of the Neath Valley Disturbance—the same fault seen earlier separating the Sugar Loaf from the Black Mountains. This long-lived structure likely originated in the Precambrian and was later reactivated during the Variscan orogeny. Along the way, the adit of a former silica mine, abandoned in 1964, is visible on the right bank of the river, while a small limestone cave on the left bank is sometimes linked to local legend that King Arthur and his army sleep within Dinas Rock. The walk culminates at the Bwa Maen fold—“the stone bow”—where Carboniferous Limestone is folded into a large fault-controlled anticline, with fossils clearly visible in the limestone beds. The fact that all of these elements come together in one place makes this arguably the strongest geological stop in the Geopark.

Pontneddfechan: In the village of Pontneddfechan, we stop to examine an outcrop of the Farewell Rock, the thick sandstone that in modern geology marks the base of the Coal Measures. Its name comes from nineteenth-century ironstone miners, who knew that once this very thick sandstone was reached there was no point digging deeper: workable ironstone lay above, and below it the ore ran out. Reaching the Farewell Rock meant saying farewell to iron. At this site, fossil tree remains are preserved at the base of an overhanging cliff of Farewell Rock. The ribbed markings on the underside of the overhang are fossil logs of Calamites, representing a log jam within a Carboniferous river channel. Their position marks the boundary where river-dominated Coal Measures give way downward into older marine rocks below.

Henrhyd Waterfall: We stop at Henrhyd Waterfall, the highest waterfall in South Wales. The waterfall exists because the river flows directly over a fault, which has brought the very thick Farewell Rock sandstone into contact with softer layers of the South Wales Coal Measures. Differential erosion across this fault-controlled boundary has produced the vertical drop seen today. This is also a stratigraphically important site. The Farewell Rock here marks the base of the Coal Measures, and immediately beneath it lies a marine band, followed by older fluvial rocks of the Marros Group.In the nineteenth century, fossil tree trunks were discovered at the base of the Farewell Rock—just as we saw at Pontneddfechan—by William Edmond Logan. These fossils are now displayed outside Swansea Museum, and Logan later became one of the founding figures of modern geology in Canada. Mount Logan, the highest mountain in the country, is named in his honour.

Craig y Fro Quarry: After leaving Henrhyd Waterfall, we drive north through the Upper Swansea Valley, passing the National Showcaves Centre for Wales and the scientifically important Heol Senni Quarry, where early Devonian fish fossils were discovered, before arriving at Craig y Fro Quarry. The quarry lies close to the main walking route up Pen y Fan. Craig y Fro Quarry exposes a fossilised Lower Devonian river channel, providing a clear view of how the Old Red Sandstone was deposited in continental fluvial environments. The quarry is of particular palaeontological importance: early Devonian fossil land plant remains found here were the first recorded in southern Britain and form one of the best-preserved Devonian floral assemblages in the country. Four distinct plant-bearing horizons have been identified, with the lowest occurring approximately 7 metres above road level. The quarry itself is cut into a small glacial cirque, and well-preserved moraines can be seen immediately in front of the site, recording much later Ice Age activity. The site is also known beyond geology. David Attenborough filmed here for his television series Life on Earth, using the exposure to illustrate the early colonisation of land by plants.

Craig Cerrig Gleisiad: A short distance back down the main road, we stop at Craig Cerrig Gleisiad. This is one of the best places in the Fforest Fawr Geopark to experience the feel of the high mountains without a long walk. After only a short approach from the road, we are quickly surrounded by steep cliffs and open upland scenery, giving a strong sense of scale and exposure.The landscape here records a sequence of Ice Age processes. During the last glaciation, ice excavated a large bowl-shaped hollow, or cirque (cwm). After the ice retreated, a major landslip removed part of the cliff face. In a later glacial readvance, some of this landslip material was reworked and deposited as moraines on the floor of the cwm.

National Park Visitor Centre: A short stop at the Brecon Beacons National Park Visitor Centre allows time to use the facilities and to view a large 3-D model of the National Park. This provides an opportunity to place the day’s geology in a wider regional context. Using the model, we can briefly introduce the Ordovician and Silurian rocks that outcrop in the far west of the Geopark and National Park. These areas include type localities of international importance, where key rock successions were first described and defined. The Silurian Period itself is named after the Silures, the Iron Age people who inhabited this part of Wales during Roman times, linking geological time directly to human history and place.

Mynydd Illtud: From Mynydd Illtud we gain wide views across the Brecon Beacons themselves, including Pen y Fan (886 m), the highest peak in southern Britain, along with Corn Du and Cribyn. These summits give the National Park its name. Most of Pen y Fan is formed from Lower Old Red Sandstone of Lower Devonian age, while the upper part of the mountain is capped by Upper Old Red Sandstone of Upper Devonian age. Between the two lies an unconformity, with the Middle Devonian absent from the succession. The broad, clean profile of the Beacons is the result of glacial erosion during the last Ice Age. From this viewpoint, glacial moraines can also be seen on the surrounding slopes, recording the movement and retreat of ice that shaped the mountains into their present form. The mountain takes its name from Saint Illtud, a sixth-century figure traditionally regarded as a cousin of King Arthur, who is commemorated by a stained-glass window in Brecon Cathedral. An older alternative name for Pen y Fan is Cadair Arthur—“Arthur’s Chair”—a historic name that is now rarely used.

Brecon (drive-through ): As we drive through the historic town of Brecon, we cross the Usk Bridge, from where there are views of Brecon Cathedral, the remains of Brecon Castle, and The Castle Hotel. While we do not stop here, Brecon also has an important place in the history of geology. Roderick Impey Murchison stayed at The Castle Hotel while carrying out his pioneering work in South Wales. Observations made across this region played a key role in his definition of the Silurian and Devonian periods, forming part of the foundation of the modern geological timescale. As we begin to leave the town, we pass Brecon Barracks, well known for their links with the Anglo-Zulu War.

Llangorse Lake: Our final stop is Llangorse Lake (Llyn Syfaddon), the largest natural lake in South Wales. The lake occupies a hollow created by glacial over-deepening during the last Ice Age. From the lakeshore there are wide views of the Brecon Beacons, particularly the steep north-facing slopes of the range. On the hillside, a feature known locally as the ALLT marks the point where the lake would have over-spilled during glacial times, before the drainage system adjusted to its modern form. Llangorse Lake is also of major archaeological importance. It contains the only known crannog outside Scotland and Ireland, an artificial island thought to have served as a summer residence of the kings of Brycheiniog. The name Brycheiniog survives today in the Welsh name of the National Park, Bannau Brycheiniog National Park, and in the historic county name Brecknockshire.

We aim to arrive back in Abergavenny for 5:30pm.

Geology of the Fforest Fawr Geopark

|

Fforest Fawr.pdf Size : 616.06 Kb Type : pdf |